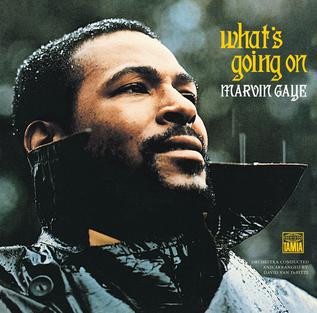

Tamla Records (T 54201)

On Monday, I was listening to Eric Nelson, defence attorney for Derek Chauvin, the Minneapolis police officer who faces three charges of second and third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter for the killing of George Floyd. Nelson was questioning prosecution witness and Chief of the Minneapolis Police Department Medaria Arradondo, who had fired all four police officers involved in George’s death.

Nelson was attempting to develop an argument that police may find themselves in difficult and dangerous situations and must make in-the-moment decisions without the benefit of 20:20 hindsight. Is it not the case, he asks Chief Arradondo, that use of force can be used as a de-escalation tactic?

His argument is slightly confused, as he gives the example of pointing a pistol, which is surely the threat of force, rather than the use of force. However, he is presumably trying to imply that neck restraint can be used to de-escalate a situation.

Co-incidentally, I was listening to Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On? (1970) the following afternoon, and the lyric:

Father, father

We don’t need to escalate

You see, war is not the answer…

And this between two other verses:

Mother, mother

There’s too many of you crying

Brother, brother, brother

There’s far too many of you dying

And:

Don’t punish me (Sister) with brutality (Sister)

Talk to me (Sister), so you can see (Sister)

Oh, what’s going on (What’s going on)

Apparently, this song was inspired by an incident of police brutality against anti-war activists witnessed by co-writer Renaldo Benson. Benson gave the song to Gaye who added his lyrics and changed the melody. Gaye in turn was inspired by the 1965 Watts Uprising in Los Angeles, where protests followed the attempted arrest of an African-American man, Marquette Frye.

Forty years exactly from the release of What’s Going On?, African American men, women and children continue disproportionately to be stopped and subject to harm from police officers in the United States. In the UK too, you are significantly more likely to be stopped and searched if you are Black, Asian or Mixed Heritage and more likely to die in custody if you are Black.

The state invests police with the legal use of violence. The use of force and restraint in order to defend self and others is a power that police necessarily wield. Occasionally, officers must make that decision instantaneously. Few would dispute that.

But it is a power which requires careful handling. Police are not meant to be a civil militia: they are peace keepers whose authority relies on public support. They are effective when they know, come from, and work with their communities; when they seek to reduce harm, to calm rather than to inflame.

In academic writing, this is often referred to as ‘soft policing’ (for example McCarthy, 2014) and draws on Joseph Nye’s (1990) work in international relations on ‘soft power’. ‘Soft’ can be deceptively strong.

Some commentators are worried that litigation and ‘political correctness’ will undermine policing. “How are police expected to carry out their job, for fear of prosecution?” they say. But this is a misrepresentation. Police officers should exercise common sense, fairness and compassion and for that, they will always be supported by the public and any jury. These are necessary attributes of the job. Individuals who want to police to enact their power fantasies need not apply.

This idea that you need to escalate, in order to de-escalate, is interesting. There is an argument that force, or risk of mutual harm, can be used to clear space for talk. But wilful and prolonged force in the absence of a threat or continued threat is not rational, fair or compassionate.

A culture where strike first and domination through suppression is prized, secures a fragile and false peace. A default escalation mentality damages policing – it means officers reach for their firearm first; it means use of a counterfeit $20 dollar bill can lead to arrest, restraint and death in nine and a half minutes.

© Natasha Mulvihill and Criminology Tales, 2021.

You must be logged in to post a comment.